🕊️ The Day the French Fleet Turned the Tide: Yorktown, 1781

When the sea became the noose — the Allied victory at Yorktown

“The world turned upside down.”

So the British musicians played as their defeated army marched out of Yorktown, Virginia, on October 19, 1781. After eight long, brutal years of revolution, the unthinkable had happened: one of Britain’s finest generals surrendered to a band of colonial rebels — and their French allies.

Yet victory at Yorktown was not won on the fields of Virginia alone. It was won at sea.

The Trap Springs Shut

When General Charles Cornwallis fortified Yorktown in the summer of 1781, he believed the Royal Navy would always be there to rescue him. The British army had dominated North America for six years, and its fleets controlled the Atlantic. Cornwallis’s plan was to hold a secure coastal base, raid Virginia’s plantations and towns, and keep open communication with General Henry Clinton’s main army in New York.

But far to the south, the tide of war was turning — carried by the white sails of France.

Commanding the French fleet in the Caribbean was Admiral François Joseph Paul, the Comte de Grasse, a seasoned naval officer whose arrival would prove decisive. In August 1781, he set sail from the West Indies with twenty-eight ships of the line and more than 3,000 troops — the largest French naval force ever seen in American waters. His mission: seal the Chesapeake and prevent Cornwallis from escape or relief.

At the same time, the Marquis de Lafayette, barely twenty-four years old, led 5,000 American troops in Virginia. Acting on orders from George Washington, Lafayette shadowed Cornwallis’s every move, skirmishing and blocking every landward path. He could not defeat Cornwallis alone — but he could hold him long enough for Washington and the French to arrive.

The Sea Decides

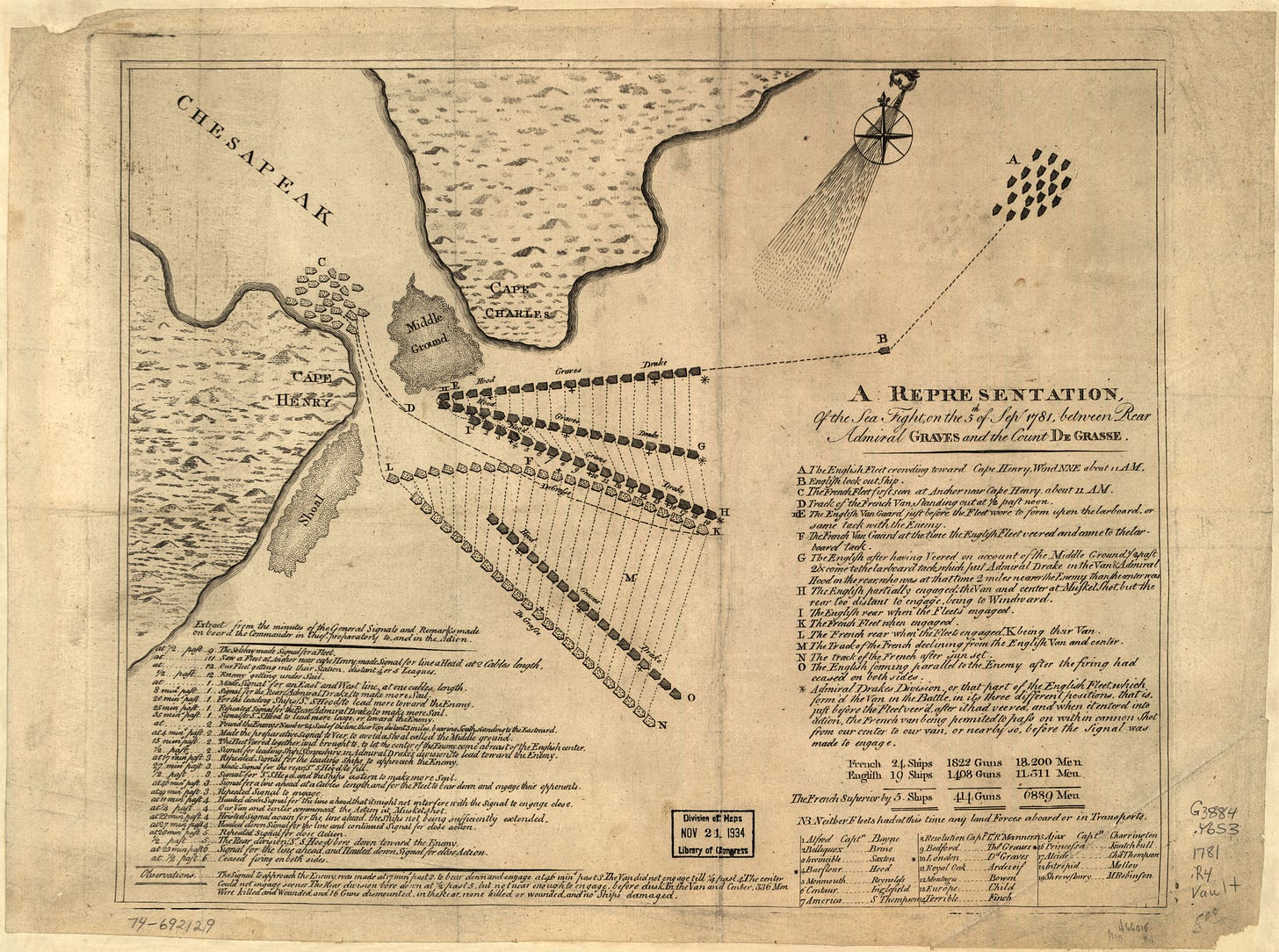

The crucial test came on September 5, 1781, off the Virginia Capes. A British relief fleet under Admiral Thomas Graves sighted de Grasse’s armada — and failed to break through. The two fleets fought for hours, cannon thundering across the waves. When the smoke cleared, the British withdrew to New York for repairs

That single encounter decided the war. The Chesapeake was closed.

Now Cornwallis was trapped: Lafayette’s troops held the land; de Grasse’s warships sealed the sea.

The Noose Tightens

Marching 200 miles from New York in just fifteen days, Washington and his French counterpart, General Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, the Comte de Rochambeau, joined Lafayette and de Grasse in Virginia. By late September, 14,000 Franco-American soldiers surrounded Yorktown. For two relentless weeks, they pounded the British defenses with artillery, advancing trench by trench until Cornwallis’s position was hopeless.

On October 19, Cornwallis surrendered his 7,000 soldiers, 900 seamen, 144 cannon, and 30 ships. He claimed illness and sent his second-in-command, General Charles O’Hara, to offer his sword to Washington and Rochambeau.

As the British troops marched out, their band struck up the mournful tune — “The World Turned Upside Down.” It was an apt choice.

The French Connection

The Revolution had begun in 1775 as an improbable rebellion against the world’s greatest empire. It ended thanks to an alliance forged by diplomacy and sustained by faith — a partnership symbolized by Lafayette’s youthful zeal and de Grasse’s command of the sea.

France’s fleet made Yorktown possible. Without it, Cornwallis would have escaped. Without Lafayette’s tenacity, Washington’s army might have arrived too late.

Together, they closed the vise — and opened the door to American independence.

Epilogue

The fighting did not end immediately; skirmishes continued on the high seas and in distant colonies. But Yorktown broke Britain’s will to continue. Within two years, the Treaty of Paris (1783) formally recognized the United States as “free and independent.”

The Revolution had lasted eight years, from Lexington and Concord in 1775 to Yorktown in 1781. Its final victory was not merely American — it was Franco-American, born of shared resolve and the power of the sea.

P.S. Next time you hear the phrase “turning the tide,” think of Admiral de Grasse’s white-sailed ships sweeping into the Chesapeake. They didn’t just turn the tide — they ended a war.

⚜️ Brought to you by John Pearce’s Paris thrillers ⚜️

International intrigue, wartime secrets, and the enduring pull of Paris.

Read a free excerpt of Treasure of Saint-Lazare →

Thanks for visiting

John Pearce

Paris

For further information

François Joseph Paul, Comte de Grasse, Marquis of Grasse-Tilly (Wikipedia)

Translation of the plaque in Saint-Roch Church:

In memory of the Count de GRASSE

In the year 1788, on the sixteenth of January, was buried in this Church the body of François Joseph Paul, Count of GRASSE, Marquis of TILLY, of the Princes of ANTIBES, Lieutenant General of the Naval Armies, Commander of the Royal and Military Order of Saint Louis, Knight of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, Member of the Society of the Cincinnati, Born at the Château du Bar, near Grasse, on September 13, 1722, Died in Paris, on January 14, 1788

By the naval victory he won over the English at the Chesapeake on September 5, 1781, Count de Grasse made possible the surrender of Yorktown, besieged by the Franco-American army under the command of General Washington and Lieutenant General Count de Rochambeau. Thus, with them, he acquired the immortal glory of ensuring the independence of the United States of America.

Requiescat in Peace

This commemorative plaque was placed by the Society of the Cincinnati of France on October 19, 1931, the one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the surrender of Yorktown, and in memory of this feat of arms whose consequences were incalculable

Great stuff, John. Thanks. We learned a lot. You'll soon be competing with Heather Cox Richardson!

Excellent, thank you