Why France Is Blocking a Trade Deal That's Flying Under the Radar Everywhere Else

Is it protectionism or basic fairness? Where you stand depends on where you sit. (Updated Friday Jan. 10, 2026)

In France, there are many ways to measure political power.

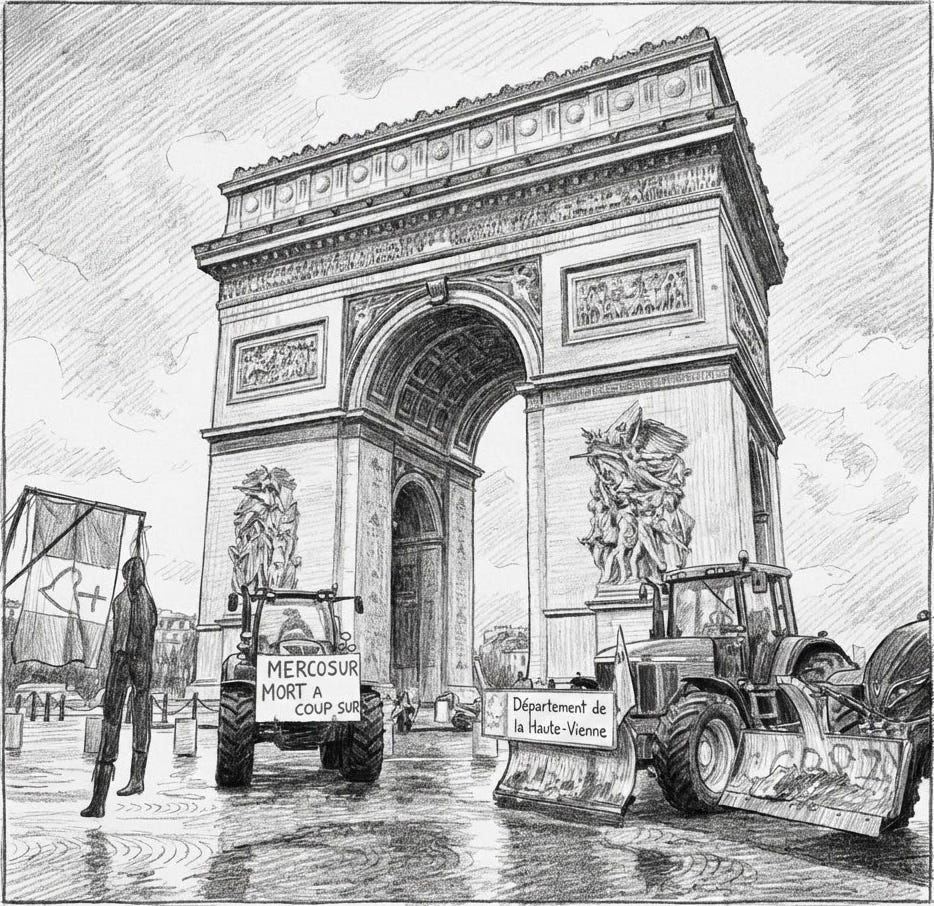

Opinion polls are one. Parliamentary votes are another. But nothing concentrates the mind of a government quite like tractors rolling into city centers.

That is why any discussion of France’s opposition to the EU–Mercosur trade agreement has to begin with a simple fact: French farmers are among the most protected — and politically influential — in Europe. And they know how to make themselves seen.

For decades, France has treated agriculture not as a sunset industry to be managed away, but as a strategic asset. Farmers benefit from generous subsidies, strict price protections, and some of the toughest regulatory standards in the world. In return, they form a powerful, well-organized constituency capable of paralyzing roads, ports, and supply chains at short notice. Presidents show up without fail at the annual agricultural exposition, when the Champs Élysées is turned into a giant farm.

So when tractors appear on the périphérique or around government ministries, Paris listens. This week it was Napoleon's famous Arc de Triomphe.

Against that backdrop, it is easier to understand why a trade agreement negotiated thousands of kilometers away has become politically radioactive at home.

What is Mercosur — and why does it matter?

Mercosur is a South American trade bloc founded in 1991, bringing together Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, and Paraguay. Together, they form one of the world’s major agricultural exporting regions, particularly in beef, poultry, sugar, soy, and ethanol.

For more than two decades, Mercosur has negotiated a sweeping free-trade agreement with the European Union. The goal is to reduce tariffs, open markets, and create one of the largest inter-regional trade zones in the world. In 2019, negotiators announced a political agreement “in principle.”

Politically, however, the deal has never recovered — especially in France.

📬 This newsletter is free

There’s no paid tier here (at least for now). Subscribing simply means you’ll receive future essays and reporting — free — as they’re published.

Why France sees Mercosur differently

On paper, Mercosur is a classic trade bargain. European manufacturers gain better access to South American markets; South American farmers gain access to European consumers. In Brussels, this is framed as economic opportunity and geopolitical diversification.

In Paris, it looks very different.

French farmers operate under some of the strictest agricultural rules in the world. Pesticides have been banned, animal-welfare standards tightened, and traceability requirements expanded — often at real cost to producers. These policies are popular with consumers and central to France’s environmental identity.

The Mercosur agreement would allow imports produced under less restrictive regimes to enter the EU market.

The French objection, repeated endlessly by ministers and farm unions alike, is blunt:

You cannot regulate your own farmers into higher costs — and then ask them to compete with imports that do not follow the same rules.

This framing matters. It transforms opposition from protectionism into a question of fairness and coherence. Farm unions such as FNSEA have been highly effective at making that case — and at reminding governments what happens when it is ignored.

(UPDATE

(The EU members voted in favor of the agreement on Friday Jan. 10. France and other countries tried but failed to lobby a “blocking minority,” but under EU rules the agreement will still have to be accepted by all 27 member countries individually for it to be effective within their borders. Ursula van der Leyen, the EU chief executive, said she planned to sign it Monday in Paraguay.

(The Buenos Aires Herald has a good wrapup today.)

The Amazon problem France cannot ignore

Agriculture alone might not have been enough to kill the deal. Climate politics finished the job.

In French debate, Mercosur has become inseparable from the Amazon. Beef exports, soy cultivation, and large-scale agribusiness in South America are widely associated with deforestation and environmental degradation. Past efforts to expand agricultural output in the region have already resulted in vast forest loss — a fact that weighs heavily in public consciousness.

For a country that styles itself as a climate leader, the optics are brutal: environmental speeches in Europe, deforestation incentives abroad.

Although the agreement contains sustainability language, French critics argue that it lacks binding enforcement. In effect, Europe would be asked to trust promises while absorbing environmental consequences.

That is a hard sell in a country where climate credibility has become a form of political capital.

The Brussels procedural fight

Adding to the controversy is a less visible but crucial dispute over how the deal should be approved.

Under EU law, trade agreements can be classified in two ways. If Mercosur is treated as an EU-only agreement, it can be approved by a qualified majority of member states and the European Parliament — meaning France could be outvoted. If it is treated as a “mixed agreement,” touching on national competences such as agriculture and environmental regulation, it would require unanimous ratification by all 27 national parliaments, giving France an effective veto.

This distinction has become politically explosive. Paris argues that bypassing national ratification would undermine democratic legitimacy, especially on an agreement with such visible social and environmental consequences. Brussels, for its part, is wary of allowing a single member state to derail years of negotiation.

The result is a procedural standoff that mirrors the deeper political one: is Mercosur a technical trade deal, or a choice with profound national consequences?

Macron’s calculation

For Emmanuel Macron, Mercosur is a rare no-win issue.

Supporting it would mean farmer protests, rural backlash, and accusations of climate hypocrisy. Opposing it carries limited short-term economic cost and aligns him with Parliament, farm unions, and a broad slice of public opinion.

This is why France’s opposition is not tactical or temporary. It is structural. Mercosur crosses too many red lines at once: agriculture, environment, and democratic legitimacy. And, he's a lame-duck president deeply underwater in the popularity polls, whose party suffered a major loss in the snap legislative elections he called last year.

More than one trade deal

In the end, Mercosur has become something larger than a single agreement. It is a test of whether Europe can reconcile ambitious environmental standards with global trade — and whether it is willing to enforce those standards at its borders.

France’s answer, for now, is clear.

Trade is welcome. Globalization is negotiable. But not at the expense of farmers who follow the rules — or forests that cannot be replaced.

Whether Mercosur ultimately passes or collapses in Brussels, it has already revealed something essential about French politics: when tractors roll and the Amazon is invoked, free trade stops being abstract — and becomes very real, very quickly.

This quick look at French affairs brought to you by:

News update from France24:

Part-Time Parisian is a reader-supported newsletter and all subscriptions are free - for now there is no paid tier

Click here to join

Thanks for the recap, John. I'm afraid the French are right, across the board. The quality of French ag products is high and so are the standards. MERCOSUR would flood the French market and indeed the entire EU market with low grade products of all kinds, often made or grown unethically. The only sore point is the main farm union FNSEA which is a stalking horse for giant agribusiness concerns. Nowhere is perfect. But god save us Europeans from a future in any way resembling that of the Americas, North and South.