When Rue d’Enfer Collapsed — and Paris Invented the Catacombs

Jan and I rented an apartment overlooking Place Denfert-Rochereau, in the calm 14th arrondissement on the southern side of Paris, for our stay this year. It's been the quartier of choice for our almost-annual trips over the last ten years because it's not as popular among tourists as the central-city areas. We don't have Notre Dame or the Marais, but we do have the métro's new automated Line 4 trains and a lot of buses, which go everywhere in a few minutes…and we can always get a seat at Café Daguerre.

As I write this I'm looking out of the sixth-floor window over one of the tree-shaded parks for which Paris is famous. All around it stand buildings dating from the late 19th century, when Baron Haussmann remade the city.

To the right I can see the new Museum of the Liberation of Paris, which opened a few years ago in one of the old gatehouses, which are the last remaining vestiges of the city wall that Louis XVI built shortly before the end of the 18th century to collect tariffs on goods imported into Paris. The Lion of Belfort statue, which I wrote about last week, is only a stone's throw away. It's a nice area.

As the end of the 1700s approached, France was in a state of ferment and the new tax regime did nothing to calm tempers. Historians cite the tariffs as one of the causes of the French Revolution, and some of the “tax farmers” responsible for collecting the tariffs fell victim to the guillotine. The octroi, a specific type of municipal tax on consumption, was especially hated.

But I digress. At the time my main story took place the revolution was still a decade in the future.

On the evening of April 17, 1774, just weeks into the reign of Louis XVI, the ground under rue d’Enfer (today part of avenue Denfert-Rochereau) gave way. A stretch of road and adjacent houses plunged into a vast void — the forgotten quarries beneath Paris. Eyewitnesses described “a frightful crash” as the earth opened its jaws.

From Roman Quarries to Hidden Voids

Paris’s geology is the root of this crisis. From the Roman period onward, Lutetian limestone was quarried south of the Seine. Initially open-pit, these quarries later extended underground as the city expanded, leaving a labyrinth of uncharted galleries. Over centuries, the memory of their locations was lost as development changed the terrain above them.

The Inspectorate and Guillaumot’s Mapping Campaign

The collapse forced action. In 1777, Louis XVI decreed the formation of the Inspection Générale des Carrières (IGC), a state agency to oversee and stabilize Paris’s underground. Its first appointed head was Charles-Axel Guillaumot (1730–1807).

Guillaumot’s mission was twofold:

Map the vast network of galleries — identifying weak points, voids under streets, and potential collapse zones.

Consolidate the tunnels — erecting pillars, vaults, backfills, and reinforcing ceilings to carry the weight of the city above.

His maps became both engineering tools and works of art — elegant cross-hatched diagrams showing interconnected galleries, shafts, and walls. If you get a chance to visit Montparnasse Tower, the walls of the viewing floor at the top show cutaways of the busy underground below Paris.

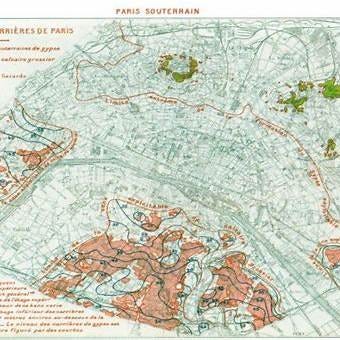

Detail from Guillaumot’s quarry mapping, Gallica/BnF.

Birth of the Catacombs: Bones in the Void

Meanwhile, Paris’s cemeteries were overflowing. The Cimetière des Innocents, in particular, posed serious sanitary risks. In 1786, the quarries under rue d’Enfer were consecrated as a municipal ossuary; bones from multiple cemeteries began their nocturnal transfers, crossing the city into the underground.

Thus a catastrophe—collapse into voids—became a pragmatically elegant solution: convert the voids into bone repositories. What we now know as the Paris Catacombs were born.

From d’Enfer to Denfert — and Later to Leclerc

The name rue d’Enfer (“Hell Street”) was medieval, probably from the Latin infernum (“lower place”), not the moral hell. It remained in use until the late 19th century.

After the Franco-Prussian War, Colonel Pierre Denfert-Rochereau, defender of Belfort in 1870–71, became a national hero. In 1872, Paris renamed Place d’Enfer and the beginning of rue d’Enfer as Place Denfert-Rochereau, the similarity in sound allowing the city to shed its gloomy old name while honoring a patriot. Over the following decades, the surrounding boulevards and avenues adopted the same name.

After World War II, the long stretch of rue d’Enfer running south from Place Denfert-Rochereau was renamed to honor General Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque, commander of the French 2nd Armored Division, which entered Paris to liberate it from the German occupiers in August 1944. Today it is the Avenue du Général Leclerc, a major southern artery, but its origins as rue d’Enfer are still remembered in the Catacombs story.

History moves slowly in the nations of the Old World. When Louis XVI became king in 1774 there had been kings of France since the mid-10th century (Hugh Capet) and kings of the Franks since the 6th. Henry IV, about whom I wrote early in September, ("Paris is worth a Mass") had been dead for two centuries. We in the United States will celebrate 250 years of nationhood in 2026, so it probably shouldn't be news that we haven't fully conquered the business of governing.

Colonel Pierre Denfert-Rochereau, Wikimedia Commons.

Cataphiles, Cataflics, and the Underground Today

The public can only access a small portion (less than one mile) of the catacombs, but hidden beneath are over 100 miles of galleries, shafts, and chambers. All of this is under the Left Bank.

This underworld attracts cataphiles — illicit explorers, map-makers, party-organizers, graffiti artists, and wandering souls. Against them stand the cataflics (quarry police), whose job is to patrol tunnels, seal illegal entries, and preserve structural integrity.

In a poetic echo of Guillaumot’s mission, the modern cataflics maintain order underground; the cataphiles push the limits of access and freedom beneath the city’s surface.

Brought to you by:

Timeline: From Quarries to Cataphiles

1st–3rd c. CE – Romans quarry Lutetian limestone south of Paris.

Middle Ages – Expansion of underground quarry galleries.

April 17, 1774 – Rue d’Enfer collapses into quarries.

1777 – Louis XVI establishes the Inspection Générale des Carrières; Guillaumot appointed.

1786 – Quarries become ossuary; bones transferred from cemeteries.

1872 – Place d’Enfer renamed Place Denfert-Rochereau.

1945 – Southern part of rue d’Enfer renamed Avenue du Général Leclerc.

20th–21st c. – Rise of cataphiles and their opponents, the cataflics.

Links

The blog Parisian Fields has an excellent rundown of the history of the catacombs. It's from ten years ago, when the Liberation Museum was still atop the Gare Montparnasse, but it's nicely done. The blog is worthwhile reading for any Paris fan.

Like any celebrity, the catacombs has its fans—many of them. They are usually called “cataphiles,” and there's a special police force dedicated to keeping them out, called “cataflics.” The Infiltration web site (“the zine about going places you're not supposed to go") has one detailed report. Youtube has many such reports. Here's one:

Thanks for reading.

John Pearce

Paris