Through the Gates of Hell: the Liberation of Buchenwald

History's Edge: What U.S. troops saw inside the barbed wire shocked the world—and changed how we remember World War II.

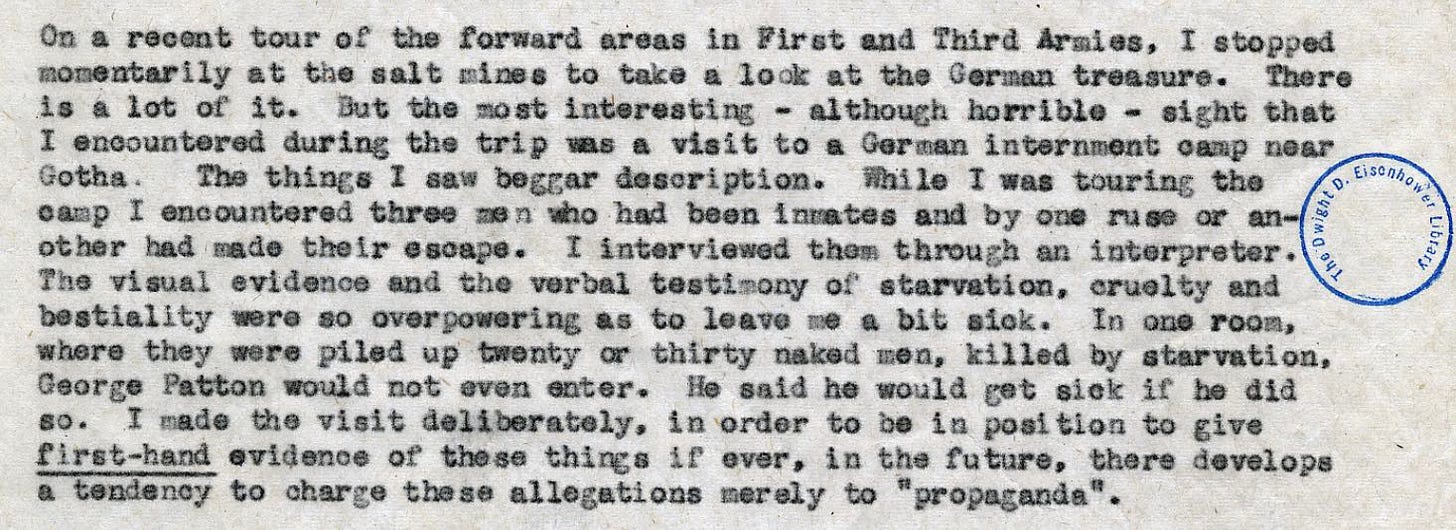

“George Patton would not even enter,” Eisenhower told his boss George Marshall in a long wrapup of his inspection tour of Buchenwald, his evaluation of the war and the needs of his military as World War II drew to a close.

April 1945 was a pivotal month. On April 11, a thin, sickly boy named Elie Wiesel was liberated from Buchenwald and would go on to a career representing oppressed peoples the world over. Earlier in the month, American troops took a smaller sub-camp named Ohrdruf, although “took” is not quite the right word. The SS knew Eisenhower was coming for them and began in late March to dispatch the camp's prisoners on ghastly death marches, then fled behind them in order to avoid the fate they knew would be theirs.

Buchenwald and its associated camp lay nestled in the forested area around Erfurt, in eastern Germany between Leipzig and Frankfurt am Main, where I lived for three years as a journalist. The area fell into the Soviet zone after the war, and Eisenhower was determined to record for posterity the conditions he found there.

After his visit to Ohrdruf, he told Marshall that Patton (who was a known tough guy) could not stomach the camps. In that letter he wrote,

I made the visit deliberately, in order to be in position to give first-hand evidence of these things if ever, in the future, there develops a tendency to charge these allegations merely to ‘propaganda.’

Buchenwald was not a pure death camp, although many died there. The Nazis had enough awareness of PR to put most of the extermination camps (Auschwitz and Treblinka come to mind) in occupied Poland, not in the homeland. The Red Army liberated Auschwitz-Birkenau two months before Buchenwald. The Germans closed Treblinka after a prisoner uprising in 1943. By the time the Red Army reached the site in 1944 it was plowed ground and some buried remains.

To the American Army and population, the liberation of Buchenwald marked one of the most searing revelations of the Nazi regime’s crimes—and a turning point in how the world would remember the Holocaust.

By early April, as Allied forces closed in, the SS began evacuating the camp—sending thousands of prisoners on death marches. But the Americans were too close. On April 11, the remaining guards fled, and a prisoner resistance group, secretly armed with weapons they had managed to hide, rose up and took control of the camp. When American troops arrived later that day, they were met not by a guarded prison, but by survivors waving white flags and a vast horror that defied comprehension.

One of the first U.S. commanders to enter the camp was Colonel Hayden Sears. The sights and smells that greeted him and his men would haunt them for the rest of their lives. Emaciated figures—living skeletons—staggered out of barracks and tents. The crematorium was still warm. Piles of corpses lay unburied. Children, many of them orphans, huddled in corners. Some prisoners, barely clinging to life, looked up at the Americans with an expression of disbelief—salvation had come at last.

One of those witnesses was Elie Wiesel, a teenage Jewish boy from Romania who had arrived at Buchenwald just months earlier after surviving Auschwitz. In his memoir Night, Wiesel recalls the moment of liberation with haunting clarity. “Our first act as free men,” he wrote, “was to throw ourselves onto the provisions. That’s all we thought about. No thought of revenge, or of parents. Only of bread.”

But it wasn’t just the prisoners who were changed. The American soldiers who walked through those gates on that spring day were fundamentally altered by what they saw. Many had spent months in combat, but nothing prepared them for Buchenwald. Eisenhower, upon visiting other camps soon after, insisted that the horrors be documented—photographed, filmed, written down—so that no one could ever deny what had happened.

The liberation of Buchenwald quickly became international news. Journalists were invited in, including Edward R. Murrow, whose radio broadcast describing the camp remains one of the most chilling accounts of the Holocaust ever aired. Murrow’s voice broke as he described the “rotting bodies piled in the courtyard” and the smell that “sickened even the strongest of stomachs.”

More than liberation, the moment marked a moral awakening. The Allies had always known the Nazis were cruel, but the systemic, industrial-scale dehumanization revealed in places like Buchenwald brought home the full scale of the evil they had fought against. For many soldiers and journalists, it was the most important story they would ever tell.

Today, Buchenwald is preserved as a memorial and museum. The rusted gates still bear the infamous slogan “Jedem das Seine”—“To each his own”—a grotesque mockery that the Nazis painted above the entrance. But beyond those gates lies a testament to human resilience. Survivors like Wiesel went on to become powerful voices for justice, ensuring the memory of the Holocaust would not fade.

The liberation of Buchenwald wasn’t the end of the war, but it was the moment the world began to understand what the war had been not only the clash of armies or ideologies, but the defense of humanity itself. The soldiers who liberated the camp didn’t just defeat fascism—they bore witness. And through their testimony, the dead found voices, and the living found a mission: to remember, and never forget.

For Eisenhower himself, there was a personal load to carry. He was quoted as saying, “I couldn’t believe my name was Eisenhower.”

LINKS

Eisenhower letter to Marshall April 15, 1945

For a liberation timeline, see this site from the Holocaust Encyclopedia. The “Must Reads” dropdown on the home page will repay you for your time.

The story of Elie Wiesel (Wikipedia)

Thanks for reading

John Pearce

Washington, DC

History's Edge is brought to you by my novel series The Eddie Grant Saga. The first book, Treasure of Saint-Lazare, is set partially among the Nazis who occupied and governed Poland. Readers’ Favorite named it the top historical mystery of its year. I have set the Kindle edition to 99c today and tomorrow (4/10-11).

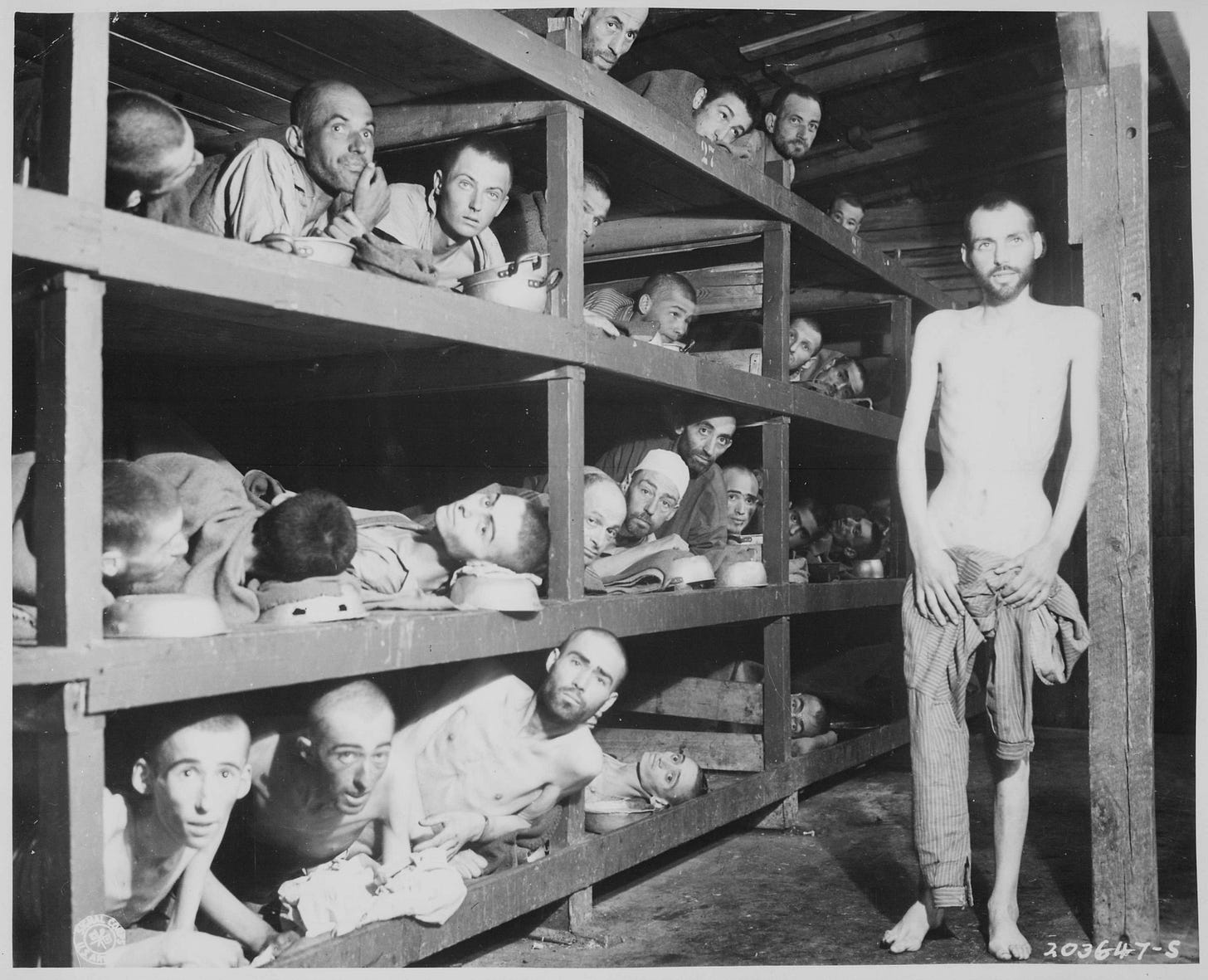

The fruit of man's inhumanity to man.

This photo from the Office of War Information shows the bunk setup at Buchenwald. Elie Wiesel is on the second level, seventh from the left, next to the vertical post.

The original caption said: "These are slave laborers in the Buchenwald concentration camp near Jena; many had died from malnutrition when U.S. troops of the 80th Division entered the camp."