The Waterway That Rewired a Nation: Erie Canal at 200

On October 26, 1825, New York uncorked a 363-mile water highway that crushed freight costs, turned farm towns into boomtowns, and pushed the American market west. Its wake reshaped Buffalo and Rochester, plugged Geneva into the world via the Cayuga–Seneca Canal—and later helped seed a hotbed of women’s-rights activism.

A five-day shortcut through the mountains

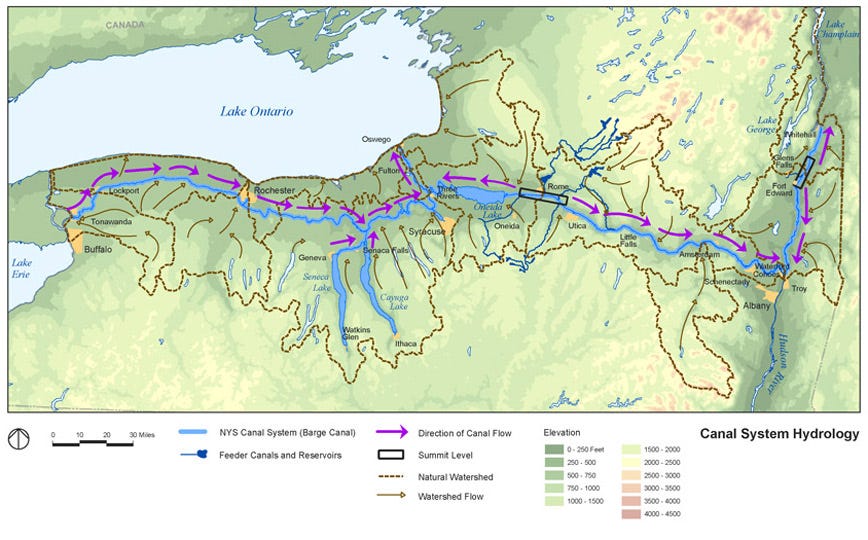

The original Erie Canal climbed roughly 571 feet with 83 locks from the Hudson to Lake Erie—an audacious bet that the Mohawk Valley gap could serve as a low doorway through the Appalachians. Engineers didn’t tunnel so much as bridge and step their way west: stone aqueducts carried boats over rivers, and staircase locks surmounted the escarpments, culminating in Lockport’s famed “Flight of Five.” The payoff was immediate: travel times fell from weeks to days, and freight costs collapsed from roughly ~$100/ton to under $10/ton.

“The canal made the corridor; the rails captured the corridor.”

One of my novels in progress is set in upstate New York. Jan and I spent a month there last year as part of our move from Florida to Washington, partially for research and partially to sample the famous Finger Lakes wines.

By the Numbers: A Corridor Rewired

Distance & Locks: 363 miles; 83 locks; ~571 ft total lift.

Travel Time: ~6–10 days by canal vs. ~2–3 weeks by road (Albany↔Buffalo).

Freight Cost: ≈ $100/ton (pre-canal) → < $10/ton soon after opening.

Aqueducts: ~18 stone spans carried boats over rivers like the Genesee at Rochester.

Build Cost: ≈ $7.1M; repaid within about a decade via tolls & earmarked revenues.

Buffalo & Rochester: Before → After

The canal’s western terminus turned Buffalo from a war-scarred village into a Great Lakes entrepôt: 2,095 (1820) → 8,668 (1830) → 18,213 (1840).

At the Genesee crossing, Rochester vaulted from 1,502 (1820) to ~9,200 (1830) and became the “Flour City.” Water-powered mills + cheap barge rates = one of the century’s clearest market-access booms.

Geneva’s On-Ramp: The Cayuga–Seneca Canal

Geneva sits on Seneca Lake, linked to the Erie via the Cayuga–Seneca Canal. That connection let lake traffic—grain and lumber at first, then fruit, vineyards, and nursery stock—flow straight into the Erie trunk line and down to Atlantic markets. The same corridor knitted together ideas and people, laying tracks (first on water, then on rails) for the reform ferment that followed.

From Waterway to Woman’s Voice

Downstream at Seneca Falls (1848), the Women’s Rights Convention set a national agenda, and by the 1890s Geneva’s Political Equality Club was one of New York State’s largest local suffrage groups. The canal corridor carried wheat and lumber—but it also carried platforms, pamphlets, and organizing energy.

Who Paid—and Why It Passed

Washington sat out; New York built the Erie with a dedicated Canal Fund (1817) that issued bonds and serviced them from canal tolls and earmarked revenues (notably Onondaga salt duties, auction duties, and a steamboat passenger tax; a special property tax within 25 miles was authorized but held in reserve). The model insulated the project from day-to-day politics and reassured investors.

Politically, “Clinton’s Ditch” drew both zeal and scorn. The most telling pivot came from Martin Van Buren: wary at first, he backed the 1817 enabling bill after improved surveys and revenue math—an early masterclass in pragmatism.

Rails on the Water Road

In 1831 the Mohawk & Hudson Railroad opened to shave time off the Albany–Schenectady stretch—pitched as a helper to the canal. As lines multiplied along the same corridor and consolidated into the New York Central (1853), trains took passengers and winter freight, forcing New York to enlarge and later rebuild the canal as the Barge Canal. The corridor the Erie created became the rails’ natural runway.

“Tolls repaid the debt; trade repaid the state.”

You are unlikely to find a better essay on the Erie Canal and its importance in American History than the one George Will published in The Washington Post last week. See it at this link.

The expanded canal: The main canal is the backbone of a network of subsidiary canals connecting the Finger Lakes and the Great Lakes. The modern lock below is on the Seneca Falls Canal near Waterloo, NY. It connects Seneca and Cayuga Lakes to the main canal. See the Erie Canalway site.

Thanks for reading.

John Pearce

Paris

You and Heather Cox Richardson are on the same page! Fascinating story.