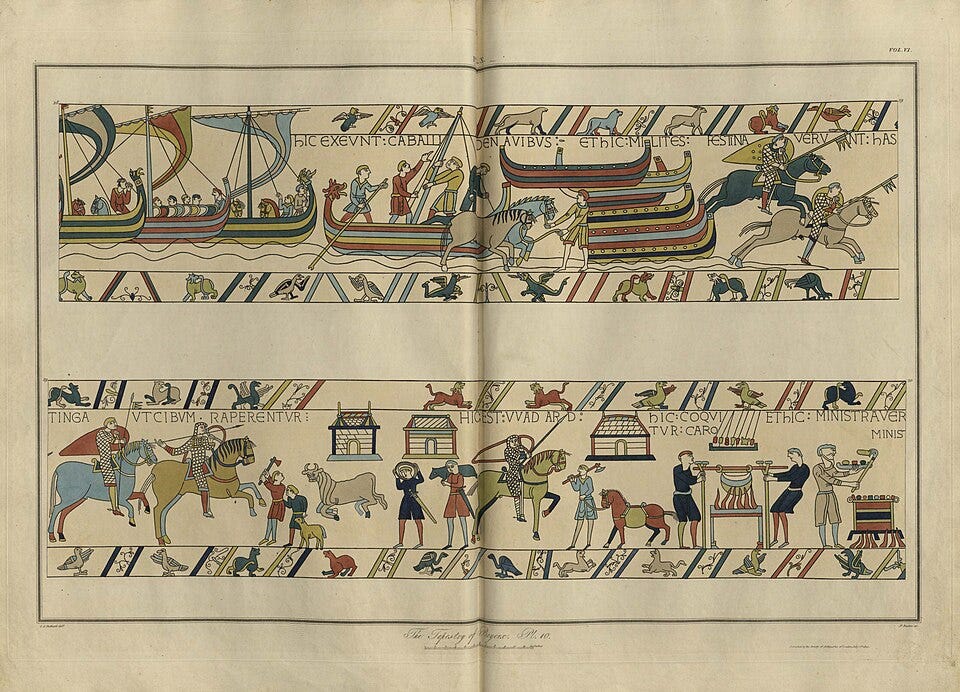

The Bayeux Tapestry’s Delayed Crossing

An update to my earlier post.

When I stood beside the narrow creek at Dives-sur-Mer on the coast of Normandy, I tried to imagine the bustle of 1066: boats lined up along the estuary, soldiers waiting for the wind, William the Bastard calculating whether this was the moment to risk everything on a Channel crossing. Today the creek is quiet, more a symbol than a harbor, but the memory of that departure lives on.

It is fitting, then, that the Bayeux Tapestry — the great embroidered chronicle of the conquest — now faces a journey of its own. When I last wrote about it, the word was that the tapestry would soon travel to London for an exhibition at the British Museum. The news sounded straightforward, almost routine: pack it, ship it, display it.

The reality has turned out to be far more cautious. The tapestry has already been removed from the Bayeux Museum, but not for loading onto a truck bound for Calais. Instead, it has been placed in secure storage, awaiting a carefully staged operation that will not be attempted until next year. Before the original ever moves, a full dry run will be conducted with a facsimile, testing every stage of the process — removal, handling, transport, vibration control, climate regulation — so that no unknown risk lurks in the shadows.

This change of plan underscores just how fragile the tapestry is. It may be nearly a thousand years old, but it is not indestructible. Conservators warn that even the smallest variation in humidity or a moment’s jolt on a loading ramp could cause irreversible damage. Hence the mock transport: an invisible army of engineers, curators, and restorers rehearsing their choreography with a stand-in before they dare to touch the real thing.

Striking parallel

I find the parallel striking. William’s fleet, massed at Dives, had to wait out storms and shifting tides before attempting its own crossing. The risks then were the sea and the weather; the risks now are vibration, dust, and the faint crackle of ancient fibers under strain. In both cases, there is no margin for error.

The tapestry’s eventual arrival in London will be a triumph of planning and patience, much like William’s eventual landing at Pevensey was the result of persistence and timing. For now, though, it remains at rest, guarded in silence, as experts rehearse the long journey ahead.

History is never as simple as it looks in headlines. Just as Dives-sur-Mer is remembered as William’s departure point — even though storms later forced him to move north to Saint-Valéry — so the Bayeux Tapestry’s voyage is more complicated than “museum lends artifact.” What we’re watching is not just the movement of a textile, but the slow, deliberate unfolding of a story that began nearly a millennium ago, on the very shore where I stood.

Thanks for reading.

John Pearce

Paris

This update brought to you by:

More to read:

Le Figaro (French): https://www.lefigaro.fr/culture/patrimoine/tapisserie-de-bayeux-le-voyage-en-angleterre-sera-organise-a-blanc-avec-un-fac-simile-20250922

Tapestry moved in advance of its loan to British Museum (French): https://www.lemonde.fr/culture/article/2025/09/19/la-tapisserie-de-bayeux-a-ete-deplacee-en-toute-discretion-avant-son-pret-au-royaume-uni_6641923_3246.html

A delicate operation indeed! I love the Bayeux Tapestry and frankly it makes me nervous to think of all that could go wrong in the transport to London. The trial run is a good precaution but really, ws this all necessary? Good piece, John. Thanks.

Don't let them eat cake. Let them view a facsimile! (I continue to hope the original stays safely in storage).