Secret Heroes: Virginia Hall and the Art of Not Being Seen

'La Femme Qui Boite' and Cuthbert

First in a weekly series about the agents who served behind the German lines in Europe. The most famous woman, Virginia Hall left Baltimore for Europe after education in several well-known East Coast colleges and wound up working for the American diplomatic service in Poland and then Turkey. It was in Turkey that she tripped while bird hunting and shot herself in the left foot. The wound led to gangrene, amputation of the leg, and then Cuthbert, her prosthesis.

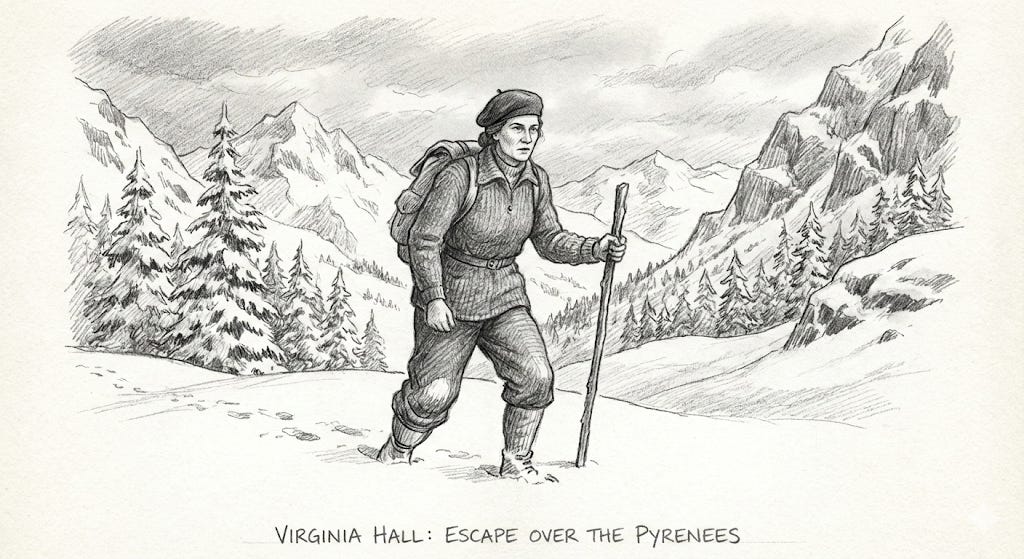

She worked in Lyon through most of 1941 and 1942, until the Germans dropped the polite fiction of an independent Vichy and she sensed the walls closing in. She took a train to Perpignan and, with a guide, walked across the challenging Pyrenees into Spain. Cuthbert was not a help, but she made it.

Next week, the post will be devoted entirely to Virginia Hall.

She should never have been there

She was an American woman, operating alone inside occupied France.

She walked with a limp.

She carried no uniform, no rank, and no protection.

By the time the German security services realized who she was, it was already too late. In internal memoranda, the Gestapo described her as “the most dangerous of all Allied spies.”

Her name was Virginia Hall.

An unlikely spy

Virginia Hall did not fit the profile of a wartime intelligence officer — at least not by the standards of the 1930s.

A hunting accident years earlier had cost her part of her left leg. She wore a prosthetic, which she jokingly called Cuthbert. She was not a soldier. She was not young by intelligence-service standards. And she was a woman in a profession still dominated by men who believed that espionage required physical perfection and official cover.

What Hall did possess was more valuable: fluency in French, cultural fluency in Europe, and an ability to disappear into ordinary life.

When war came, those qualities mattered more than rank.

Living underground in France

Hall entered France in 1941, before the United States had formally entered the war. She began work under British auspices, later serving with the American Office of Strategic Services. Her task was not sabotage alone, nor simple intelligence gathering.

Her job was to build an underground.

She organized resistance cells, established safe houses, coordinated escape lines for downed Allied airmen, and transmitted intelligence under conditions that made detection increasingly likely. She lived under false identities, memorized cover stories, rotated sleeping locations, and learned when not to speak.

This was not a cinematic version of espionage. It was clerical, logistical, improvisational — and lethal when mistakes were made.

Hall understood something early that many did not: survival depended less on daring than on not being noticed.

Why women endured

In occupied France, men of fighting age were routinely stopped, questioned, and monitored. Their movements were suspicious by default.

Women were not.

They were assumed to be apolitical, domestic, and harmless — an assumption that proved catastrophic for the occupying authorities. Women could move as couriers, rent rooms, circulate socially, and ask questions without attracting the same scrutiny.

Virginia Hall exploited that blind spot relentlessly.

Her limp, far from being a liability, became part of her invisibility. No one expected a woman with a prosthetic leg to be running intelligence networks. That miscalculation saved lives — and cost the Germans dearly.

Paris and the tightening net

Paris offered anonymity: crowds, movement, routine. It also offered danger.

The city was dense with German security services, French collaborationist police, informers, and radio-direction units hunting illegal transmitters. Networks were fragile. Betrayal was common. Capture often meant torture, deportation, or execution.

By late 1942, Hall’s name began appearing in German reports. Her descriptions circulated. The net tightened.

She did what experienced underground operators always did when exposure became inevitable: she vanished.

The Pyrenees

Hall escaped France on foot across the Pyrenees in winter, part of the journey on skis — a crossing that killed many who attempted it.

It was not a heroic dash. It was slow, painful, and uncertain. Her prosthetic leg froze repeatedly. At one point she sent a message describing her difficulty, dryly noting that Cuthbert was giving her trouble.

She reached Spain alive.

Most would have considered that the end of the story.

Virginia Hall did not.

And then she returned

After recovery and further training, she went back into France — this time as an American OSS officer — landing by boat and operating behind German lines until liberation. She resumed underground work, coordinated resistance units, and continued reporting until the war ended.

When peace came, her work receded into classified files.

She did not write memoirs. She did not give interviews. She went on to serve quietly in the early Cold War years, then retired without public recognition. Formal honors came decades later, long after her most dangerous work had been forgotten.

Why she matters

Virginia Hall matters not because she was exceptional — though she was — but because she reveals how the underground war was actually fought.

It was fought by people without uniforms, without guarantees, and often without acknowledgment. It was fought in rented rooms and borrowed identities, in silence and routine. It depended on the ability to pass unnoticed — and on the willingness to keep going when recognition was unlikely.

Hall was not the only one.

She is simply where this series must begin.

Thanks for reading

John Pearce

Washington, DC

About the author:

I write historical fiction set in Paris, often inspired by real events and hidden histories. If you aren't already a subscriber, click the button below to join.