Paris Is Worth a Mass: Henri IV’s Vision for a Reborn France and a Remade Paris

A wedding gone wrong and the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre

On an August morning in 1572, a young Protestant prince walked up the nave of Notre-Dame to marry a Catholic princess. Within a week, Paris ran red—and the survivor of that wedding would spend the rest of his life trying to heal the wound and rebuild the city that nearly killed him.

A wedding that lit the fuse

On August 18, 1572, Henri de Navarre (the future Henri IV) wed Marguerite de Valois in Notre-Dame. The marriage was meant to cool France’s religious civil wars by joining a leading Huguenot to the royal Catholic line. Instead, it set off one of the most infamous sprees of sectarian violence in European history. In the early hours of August 24–25—the feast of Saint Bartholomew—mobs and royal guards fell upon Protestant leaders gathered in Paris for the celebrations. Admiral Gaspard de Coligny was murdered, his body thrown from a window; killings then spread citywide and, soon, to provincial towns. Contemporary estimates vary widely, but thousands died.

Henri himself escaped the fate of his co-religionists only by outwardly abjuring Protestantism and remaining a quasi-captive at court. Four years later, he slipped away, reconverted, and resumed leadership of the Huguenot cause—an early hint of the pragmatism that would define his reign. Wikipedia

Henri did what he could to reconcile the hot religious feelings, but the split between Catholic and Protestant was more emotional—and potentially lethal—than it is today. Henri's end came at the hand of François Ravaillac on the little Rue de la Ferronerie, which passed by the Innocents Cemetery and is now in the Halles district near Châtelet, steps from the Seine.

It's an area I know well and have been visiting for years; in fact, Jan and I are in Paris as I post this. It plays an important role in my forthcoming novella Paris Fling as the site of a romance between two Americans, both former CIA agents who keep their checkered pasts secret from each other until it's almost too late. The Café Amazon where they meet is lifted directly from the Amazonial, just across the street from the spot where Henri was assassinated. It's one of my favorite places. Tell Thierry I sent you.

“Paris is worth a Mass”

When a domino-line of royal deaths finally made Henri heir in 1589, France’s Catholics balked at a Protestant king and the wars dragged on. In 1593 Henri famously converted—“Paris is worth a Mass,” he’s said to have quipped—and set about unifying the realm. Five years later, he issued the Edict of Nantes (1598), a practical compromise that affirmed Catholicism as the state religion while granting limited worship and civil rights to Protestants—enough breathing room to cool the wars that had consumed France for decades. (Louis XIV would revoke it in 1685.)

The builder-king

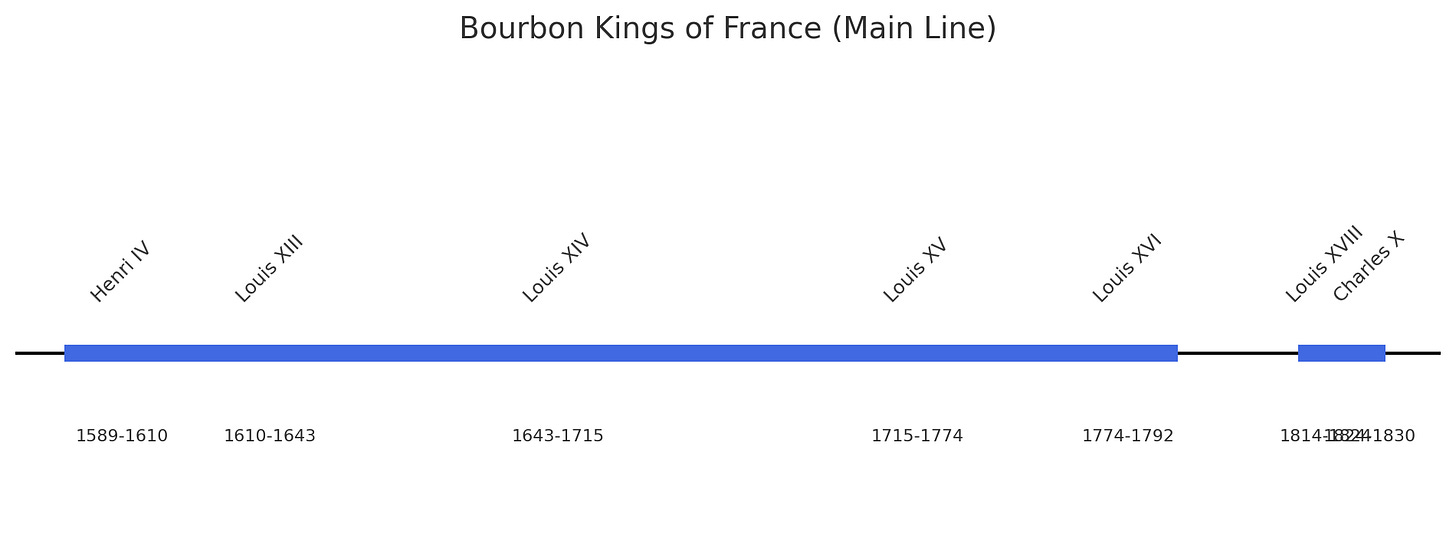

Henri was the first of the Bourbon kings, who shaped France’s transition from medieval monarchy to modern nation, with Henri IV and Louis XIV as the most emblematic rulers.

Henri IV’s gift was not austerity but abundance. He pushed agriculture, trade, and manufacturing (even seeding a Paris silk industry) and, crucially for us walkers, remade the city’s fabric. Three Paris places let you “meet” him today:

The Louvre’s Grande Galerie. In the 1590s Henri commissioned a 460-meter riverside wing to link the medieval Louvre to the Tuileries. Though later altered, this audacious gallery announced a king who thought—and built—on a grand scale. Bonjour Paris

Place des Vosges (Place Royale). Begun in 1605 and finished in 1612, it was among Europe’s first planned squares: brick-and-stone uniformity, vaulted arcades for merchants, steep slate roofs, a perfect garden at center. Henri envisioned artisans living above workshops and selling beneath the arches—urban planning married to commerce. Bonjour Paris Wikipedia Le Marais Mood

Pont Neuf and the statue of Henri IV. The “New Bridge” was opened to traffic in 1604 and inaugurated in 1607—broad, house-free, with those unforgettable mascaron faces. The equestrian statue you see mid-span was set on its base in 1614 (destroyed in the Revolution, replaced in 1818), a bronze punctuation mark to the king who bound the city’s banks together. Wikipedia

Henri’s Paris was not only streets and stones. It was a social promise as well—“a chicken in the pot on Sundays”—and a political compromise that prized peace over purity. Bonjour Paris

Blood on the route, and where it led

Two plaques close the circle of his Paris story:

Rue de la Ferronnerie (1st). Here, blocked by traffic in his carriage on May 14, 1610, Henri was stabbed to death by François Ravaillac, a religious fanatic. The discreet plaque still chills. Wikipedia

Basilica of Saint-Denis. North of the city, the royal necropolis holds Henri’s tomb, a sober counterpoint to his exuberant life.

Walk it today: A short, self-guided loop

Notre-Dame (Parvis). Picture the 1572 wedding procession and the uneasy truce it tried—and failed—to forge.

Louvre Cour Carrée → along the Seine to Pont Neuf. Think of the Grande Galerie knitting palace to palace—and realm to realm.

Pont Neuf midpoint. Salute le bon roi Henri on horseback and scan the mascarons on the arches below.

Square du Vert-Galant (tip of Île de la Cité). A pocket of calm named for Henri’s “green gallant” reputation.

Rue de la Ferronnerie. Find the plaque that marks the assassination.

Option: Metro to Place des Vosges for one of Europe’s most harmonious squares—Henri’s civic ideal made brick.

(Practical notes: Pont Neuf—M° Pont Neuf or Cité. Place des Vosges—M° Saint-Paul or Chemin Vert. Saint-Denis—RER D / M° Basilique de Saint-Denis.)

Why this story matters

The Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre is a cautionary tale of what happens when fear marries faction and the center does not hold. Henri IV’s answer—imperfect, reversible, thoroughly human—was to choose peace, build boldly, and invite prosperity to crowd out fanaticism. Paris, in other words, was “worth a Mass,” a market, and a magnificent square.

Why “le Vert-Galant”?

Henri IV’s nickname, le Vert-Galant—literally “the Green Gallant”—captured his reputation as a vigorous and amorous king. In early modern French, vert meant youthful vitality, while galant suggested charm, gallantry, and romantic appetite. The phrase implied a man still lively in love, even into age.

You’ll find his memory anchored at the Square du Vert-Galant, the little park at the western tip of Île de la Cité. Nestled beneath Henri’s equestrian statue on Pont Neuf, it’s a quiet spot where Parisians picnic, watch the Seine currents meet, and recall the king whose heart—and legend—never grew old.

Further reading & sources

Marian Jones, “Henri IV’s Legacy in Paris,” Bonjour Paris — a lively primer and a perfect companion for your walk. Bonjour Paris

Overviews of the Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, Coligny’s murder, and aftermath. Wikipedia Encyclopedia Britannica

On Henri’s captivity, escape (1576), and later conversion/Edict of Nantes (1598). Wikipedia Encyclopedia Britannica Musée protestant

Dates and details for Place des Vosges and Pont Neuf. Wikipedia

Is it or isn't it the head of Henri IV?

The purported head of King Henri IV of France—a long‑lost relic tangled in mystery and controversy—first resurfaced in 1919.

When and where was it found?

At an auction in Paris (1919): A photographer named Joseph‑Émile Bourdais purchased an embalmed, mummified head for just three francs at an auction held at Hôtel Drouot in Paris. He spent his life trying to prove it was the king’s. The Guardian Phys.org

In an attic in Angers (2008): The same head re-emerged when it was discovered inside a box in the attic of a house in Angers, western France. The homeowner, Jacques Bellanger, said he'd bought it in 1953. The Guardian myfrenchlife.org

What followed?

In 2010, forensic studies led by Philippe Charlier and colleagues suggested the head could indeed be Henri IV’s—pointing to anatomical features like a nostril mole and a healed facial wound seen in portraits, along with tomography-based facial reconstructions: they claimed “99.99% certainty.”

However, later DNA analyses cast serious doubt on the claim. The Leuven research team concluded there was no genetic match between the head and living Bourbon descendants, suggesting the head probably is not Henri IV’s.

Thanks for reading.

John Pearce

Paris

Brought to you by

Treasure of Saint-Lazare, the key volume of my Eddie Grant Series of Paris thrillers. Chosen best historical mystery of its year in the Readers’ Favorite writing contest.

Interesting, informative and a good read.