Oct 7, 1944 — The Day Auschwitz Fought Back

On this day in 1944, Jewish prisoners forced to work in the crematoria at Auschwitz-Birkenau—the Sonderkommando—staged a desperate revolt. Gunfire cracked across the camp as prisoners attacked guards, set buildings ablaze, and blew up Crematorium IV with powder smuggled in spoonfuls from a munitions factory. SS units crushed the uprising within hours and executed those they could seize. Yet for a few electric minutes, the machinery of murder stalled—and the world was left a record of armed resistance inside a death camp.

The rebellion in the death camp was more than a year in the making. In cooperation with the Polish resistance, detailed plans were made to overpower the SS guards, cut the fencing around Auschwitz and Birkenau, and blow up one of the crematoria with powder smuggled in by six women prisoners. The National World War II Museum of New Orleans has one of the most detailed and specific articles on the uprising I have seen, and I recommend that you read it at this link.

Höss’s shadow—and the film that makes us listen

If you’ve seen The Zone of Interest (2023), you’ve met Rudolf Höss as a chilling bureaucrat of normality—gardens and family picnics within earshot of gas chambers. Höss was not commandant on the day of the revolt (that office had passed from Arthur Liebehenschel to Richard Baer), but the system he helped build still ruled the place. In mid-1944 he even returned to supervise the Hungarian deportations. The film’s power is precisely that continuity: evil as routine, carried on beyond any one man.

What happened to Höss afterward: He left the commandant’s post in late 1943 for the SS camp inspectorate, was captured by the British in 1946, testified at Nuremberg, was extradited to Poland, and hanged at Auschwitz on April 16, 1947.

Where Auschwitz stands among the camps

Auschwitz was a complex: a concentration and labor camp (Auschwitz I and Auschwitz III/Monowitz) plus the killing center (Birkenau). The Operation Reinhard sites—Bełżec, Sobibór, Treblinka—were built almost solely to murder, with tiny prisoner detachments forced to keep the process running. More than 1.1 million people were killed at Auschwitz, nearly a million of them Jews; the Reinhard camps murdered roughly 1.5 million Jews within about eighteen months.

The numbers on the arm

A detail many readers think of as a concentration camp trope—the tattooed serial number—was largely unique to Auschwitz. Early on, SS clerks used a metal stamp to punch numbers into skin with dye; later they shifted to a single-needle device on the outer left forearm. Most other German camps recorded prisoners on paper and with cloth badges, not tattoos. And those sent straight to the gas chambers at Auschwitz were never registered at all—and so were never tattooed.

Liberation between Normandy and the Red Army’s advance

From June 6, 1944 (D-Day) onward, the Allied pincers closed:

In the east, the Soviets overran Majdanek in July 1944 and reached Auschwitz on January 27, 1945, finding some 7,000 survivors left behind after hurried SS evacuations.

In the west, US and British troops liberated camps like Buchenwald (April 11), Bergen-Belsen (April 15), and Dachau (April 29), confronting famine, disease, and mass death in real time.

How survivors were treated:

Soviet-liberated areas. The Red Army established ad-hoc hospitals and fed those who could be saved, but policy routed liberated Soviet citizens through NKVD “filtration” to check for “collaboration.” Most were cleared and repatriated; some—especially POWs—were punished or assigned to forced-labor battalions. Jewish survivors in the Soviet zone generally lacked a western Displaced Persons (DP) pathway and faced increasing barriers to emigration.

Western Allied zones. Survivors moved into DP camps under US/UK military control and then UNRRA. Conditions were initially dire, but policy shifted by late 1945–48 to recognize Jewish DPs as a distinct group and to open emigration routes, culminating in measures like the US Displaced Persons Act (1948).

Aftermath and justice

The legal reckoning began with Nuremberg, then widened. In Kraków (1947), Poland tried forty former Auschwitz personnel (including ex-commandant Arthur Liebehenschel), handing down twenty-three death sentences. Britain prosecuted the Bergen-Belsen staff the same year. West Germany’s Frankfurt Auschwitz Trials (1963–65) finally put mid-level perpetrators before the public. Even so, the number convicted was a fraction of those involved, and many sentences were light.

Why this day matters

It rebuts the myth that Jews “went like lambs.” Resistance existed—in ghettos, forests, and inside Auschwitz itself.

It shows how an institution can outlive a commander: Höss’s methods persisted long after he left the office.

It clarifies Auschwitz’s place in the wider machinery of annihilation.

This glimpse of history brought to you by

Much of the action of Treasure of Saint-Lazare takes place in Krakow, 35 miles from Auschwitz. There, Hans Frank, Hitler's personal attorney and head of the Polish rump state, kept the priceless Raphael painting Portrait of a Young Man. History tells us he shipped it to his home near Munich when the Russian Army threatened Krakow from the east. It never appeared there. Frank's son later wrote a bitter biography of his notorious father and speculated that his mother traded it to a Bavarian farmer for butter. It has not been seen since.

Hans Frank was hanged Oct. 16, 1946, at Nuremberg. His ashes, like those of the other high-ranking Nazis hanged with him, were spread over the rivers of Germany to prevent them from becoming cult relics.

Treasure of Saint-Lazare was the top-ranked historical mystery of its year in the Readers’ Favorite writing competition. It has been reviewed on Amazon more than a thousand times.

Thanks for reading

John Pearce

Paris

More information

Further Reading

USHMM — Prisoner Revolt at Auschwitz-Birkenau (Oct 7, 1944):

USHMM — Tattoos and numbers at Auschwitz

USHMM — Liberation of Nazi camps

National WWII Museum — The Sonderkommando Uprising in Auschwitz-Birkenau

Film — The Zone of Interest

Where were the camps?

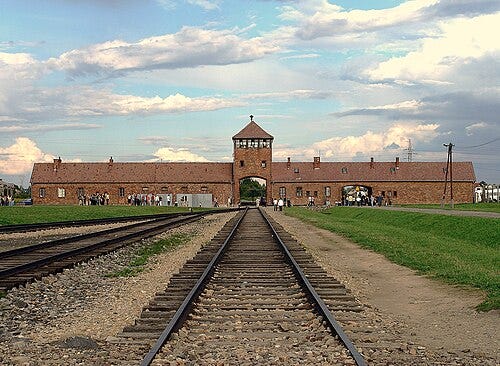

The iconic image of the tracks on which the deportees arrived (taken from inside the camp)

Fascinating, John. I was unaware of this tragic, heroic episode.